Content Warning: This article has mentions of suicide.

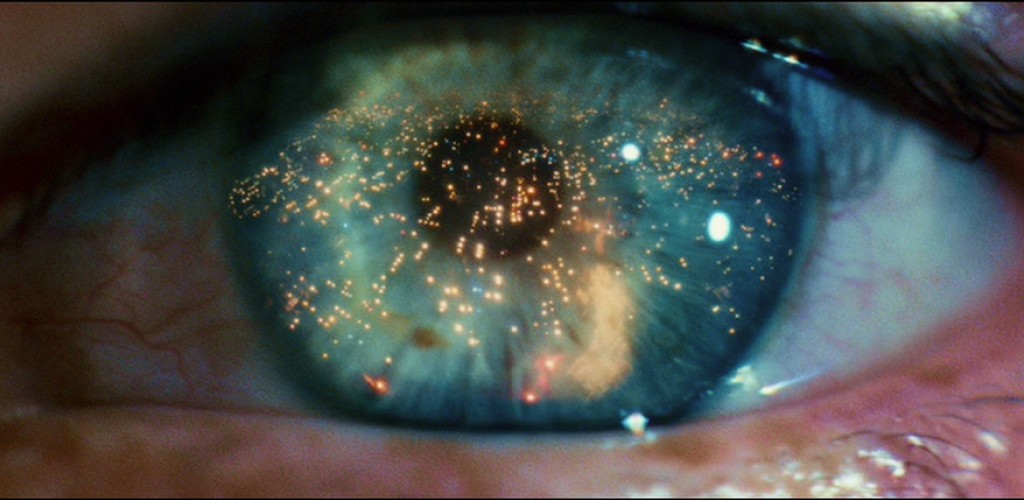

“You look lonely, I can fix that.”

Words whispered by a gargantuan pink holographic woman to a sad broken man. His beat up and bloody face, her full black iris-less eyes. Her words pierce and feel special, she is a repeated advertisement for an AI companion, a beautiful one.

The above scene is Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 that sets the stage for what this article is looking to explore. Why are advertisements such a recurring theme in science fiction movies? If it were another genre of movie like a murder mystery or a comedy, we would rarely see an advertisement playing a crucial role in the world-building, so what is different about science fiction?

Advertising always reflects the society it’s made in. Whether it’s through challenging the norm or perpetuating the stereotype. In a lot of science fiction, there exists a dystopia, a world where things have drastically changed. Advertisements can be used to get the world building and narrative on its feet quickly. An ad with a holographic woman? Humankind is more technologically advanced than the current time. Real estate for colonies on Mars? Commercial space travel is available for characters in the film to use.

A genre that heavily relies on world-building needs all it can to make it as immersive as possible to audiences. So what about the disconnect then? Often the tone of the advertisement contrasts to the ethos of the society.

A movie that nails the “society vs. advertising” disconnect is Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men. In Cuarón’s dystopian England, humanity can no longer reproduce, and infertility is a pandemic that has destroyed the world. Refugees of the world are locked away in horrific cities whilst the rich live comfortably with the highest of luxuries. The movie’s main premise is that the main character, Theo, who lives a less-than-ideal, depressing grey life, is tasked to escort the world’s fate to safety—a pregnant woman.

Right after we see the gruelling conditions of refugees in cages, the shot pans to Theo walking away and then we catch a glimpse of an advertisement.

In this scene we see the electronic board advertise “Forever Young Medical Surgery.” An advertisement that is so contrasting and unrelated to the situation we just saw that it makes us realise the disparity that has enveloped humanity. Something we can relate to, seeing ads for things we don’t need constantly and in the same breath the amount of plastic waste in the ocean. It disrupts our emotional regulation to the point where we become disconnected.

In another scene, Theo wakes up and an ad for the state-assisted suicide product/programme known as “Quietus” is playing.

“Quietus is a narrative, worldbuilding prop that helps us understand the world of the story. It helps us to understand that people are so desperate and depressed they are willing, at mass scale, to consider suicide. It helps us to understand that the government is facing such a terrible lack of resources that it has to incentivize this suicide to keep its population to some manageable level, to those who can still press on. It helps to underscore how important the sound of children’s voices are to most of the world’s sense of hope and purpose.” — By Christopher Noessel Via Sci-Fi Interfaces

The ad is jarringly gentle and soft for an act that would be widely considered unethical today, yet it shows how society’s norms have changed due to humanity’s inability to reproduce.

In another fleeting shot, we see an advertisement for “Happiness In A Pill” on the side of the bus. There is a strong use of juxtaposition in these scenes. The advertisements are always preceded by a terrible display of the world. This dissonance is the key to creating a dystopia because a dystopian story works by showing a world where characters are stripped of humanity.

These are all examples from dystopian movies, but how close are we to reaching this neon future wasteland of advertising?

An ad by Panadol created a few months ago shows an overworked food delivery rider using Panadol to relieve a headache.

Strangely, it feels reminiscent of the Quietus ad. In a society where most lower-class workers are extremely overworked for very little money, the solution presented for their exhaustion is Panadol. This ad reflects our current society: delivery persons cannot take a break to rest because they need to earn enough just to get by. If a sci-fi film were to be made of these times, it would be the perfect ad to show the disparity in the 2020s.

Conclusively, there is much to be learnt about the treatment of advertising in science fiction narratives. It is an interesting and subliminal world-building prop. When we observe how it reflects the narrative we can observe how our current advertising trends are reflecting us and the status quo. It can drive change even if just on an individual level. With overconsumption at an all-time high, we have to be more mindful than ever of why these things are being advertised—and what it is saying about us.