This is part two of a three-part paper that discusses the importance of culture, history, and social behavior for designing for the future. Part one of this series can be read here.

“A month won’t be enough to cover Barcelona city,” I was told. In 2010, I took a 2-week vacation and discovered you need more than a year. On my last day, I felt downcast, knowing I had just licked the tip of this iceberg.

Barcelona is the second-most populated municipality in Spain, fifth in the European Union, and is known to hipsters for its parties, and to art lovers for its painters. I myself have four lovers there: Pablo Picasso, Joan Miro, Salvador Dali and Antoni Gaudí. It was reaching the peak of summer, from food to culture, the locals were seen as carefree, urbane, and sophisticated. “Wearing sunglasses is religion here,” one local advised and so insouciant was their temperament that they were nonchalant when my then-mother-in-law was being dotty after I mistook her to the Museum de l’Erotica (Barcelona Erotic Museum). Previously she was not one for exhibitions, but this roused her inexplicably with every blatant display. And that is what Barcelona does to you — wakes you up as well as all of your senses.

But this isn’t an article about my trip. While my adorable former mother-in-law was enthused by the phallic memorabilia, it was the city planning that wildly besotted me.

To the unfamiliar, Spain has over 50 provinces, Catalonia being its largest. While Madrid is the capital of Spain, Barcelona is one of the four provinces of Catalonia (the other three being Girona, Tarragona, and Lleida). What makes Catalonia unique is it’s independent movement. It has its own language (most noticeable outside of Spain), cultural ethics and holidays. Catalonians in the northeast are described as more business-minded, hard-working, and focused on succeeding which parallels its cooler weather compared to the exuberant, fun-loving and outgoing Andalucians of the hotter northwest. When it comes to art and architecture, Barcelona is an artist’s Mecca. Walking down the streets you can witness the Art Nouveau battle. This was the microcosm of eccentrics such as Picasso (Málaga), surrealist Dali, and architect Gaudí, the hand behind La Sagrada Familia, Casa Battlö, La Pendrera and Park Güell. But one name is often overlooked — Ildefons Cerdá.

Cerdá (1815-1876) is the “OG” (original gangster) of urban planning. His thought processing was so advanced and conscientious, it continues to put contemporary city planners to shame.

In the 1800s, Barcelona was thriving as an entrepôt that connected Europe and Asia, but the city reached a bloated point due to development of the textile sector. Eventually it became unpleasant to live in as the surrounding medieval walls became suffocating and had to go. Rising population density increased likelihood for diseases, and life expectancy had dropped to 23 years for the working class and 36 for the rich. To expand the city was a socio-political risk but to retain it was even more perilous because the bourgeois society, the working classes, and the factories were now crammed into the same social spaces. Just as Covid-19 has been our problem, Barcelona suffered a series of endemics that were just as fatal, namely cholera, killing up to three percent of the population at a time. Cerdá’s engineering solution was not to see the city’s problems for what they were, but for what a city aspires to become. He took a visionary approach and added considerate layers of humanities, communication, and social-psychology. While his methodology was painstakingly mathematical, his strategy was empathetic. For example, seeing a disparity between the rich and the poor, he identified that the rich had an average of 3.6 cubic meters of space while the poor had merely 0.9. This, he thought, needed to change because one’s comfort should never be at the expense of another. He codified this endeavor into one term “urbanization”. Details of this can be read in his General Theory of Urbanization 1867, making him the first urban planner with extensive empirical support on how to build a functional city.

The beauty of Cerdá’s work is his scrupulous appreciation for safety and sanity for physical and psychological hygiene, touch-points even by today’s standards considered advanced. To better understand his structured thinking he compared the controlled chaos of the Gothic Quarters located in the historic center of Barcelona, nestled between two streets, the famous La Rambla (fondly called Las Ramblas) and Via Laietana, the Barri Gòtic which refers to the ancient village, remnants of the Roman empire with surrounding walls and many random roads that were neither parallel nor perpendicular.

Cerdá was a utopian populist and wanted nothing more than to equally distribute the liberation that came with social spaces. “Everyone must have room to breathe” was an underpinning philosophy and it helped that Cerdá was a well-travelled man who could inject a new perspective. Contained within his magnum opus was Cerda’s systemic studies on ventilation, space, human versus nature interactivity, traffic circulation, health, etc. to name a few of his concerns. However, such noble intentions were greatly challenged. Rival architects felt suspicious of his relatively little known backstory, “Who was this civil engineer?” they queried. His focus on improved quality standards made him an outlier as they were luxuries not allocated to the poor.

Added contention came from Antoni Gaudí, the darling architect of the aristocrats. At the time, competition among the rich was for their abodes to be the tallest, biggest, and/or the most outstanding, partly to demarcate themselves from the impinging lower classes around them and to signify privileged boundaries.

While Gaudi excelled at creating spectacular designs filled with colourful, curving organic forms, Cerdá’s take on innovation was the affordability to “spread spaces out” allowing everyone breathing space.

Cerdá wanted Barcelona to be an intentional city, one that demonstrates thought, conception, and can organically grow with increased population because, a city is a growing and evolving organism. Cerdá had predicted the rise of the motor car. That’s how Cerdá created the Ensanche and Eixample. In prophetic fashion, his vision was preparing Barcelona for the century ahead.

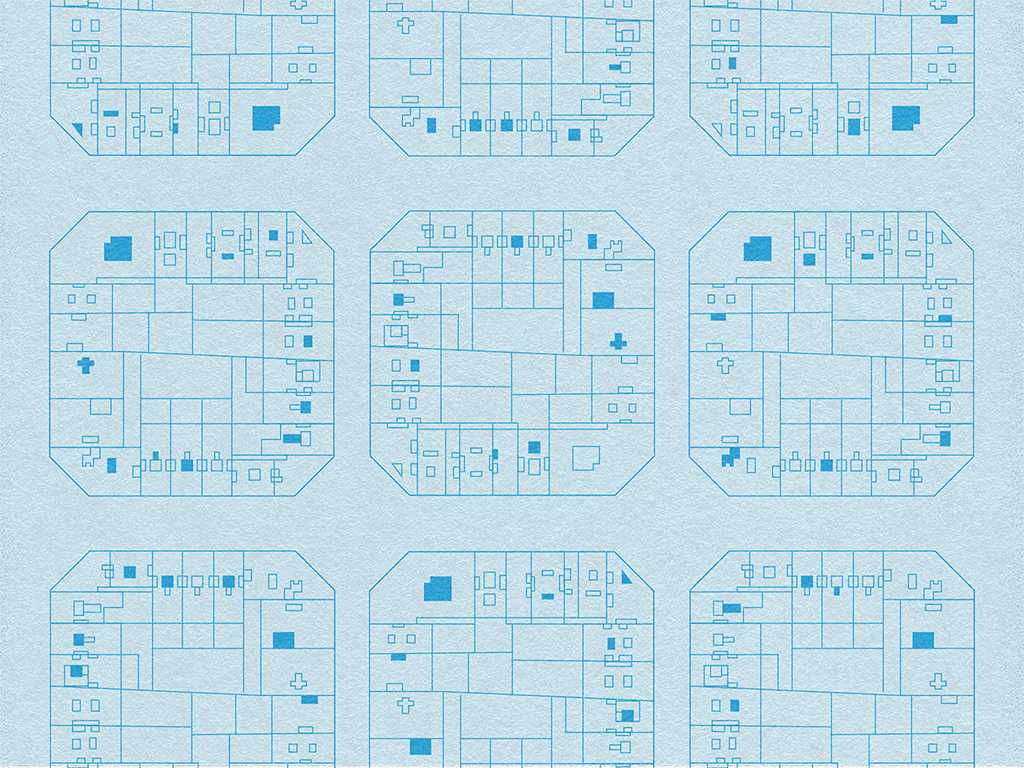

An aerial view of Barcelona city shows a distinct character—equally sized blocks in a grid matrix. Cut across these orthogonal grids were long wide streets. Each grid was a self-sustaining village based on an Eixample (expansion) model. Ensanche meaning widening, referred to the expansion project of creating space by tearing down the ancient Roman walls The idea, however, wasn’t new. The Romans called it the hypodamic plan, or hippodamian, named after their very own urban planner named Hippodamus. Described by Aristotle as “the best city”, Hippodamus carefully designed two port cities, Miletus and Piraeus, using the rectangular grid feature that could facilitate up to 50,000 people.

Scrutinizing the Eixample, a large area north of Plaça de Catalunya that spreads left and right of Passeig de Gràcia, you can better understand Cerdá’s genius. While most cities have a traditional radial design (the circle of central Rome; the outer ring road of Bangalore; Afghanistan’s Highway 01), Barcelona has a straight grid pattern. The objective is to ease navigation and to build upward. This allowed spacious and well-organized intersections with a uniform width. This idea was also in the provision for underground trains and elaborate sanitation.

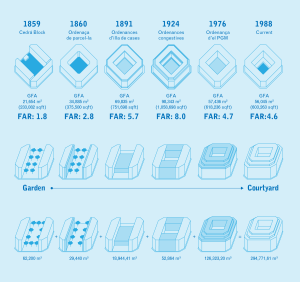

My favourite aspect of this gridiron city plan is Cerdá’s emphasis on building a shared plot of land and a design space that could provide sufficient air, sunlight, movement for pedestrians, safety, and encourage interaction and connectivity with nature. Each block (called manzana) generally had no more than three buildings in total with an expectation that many of the city blocks would have two open sides. There were three block designs: a U-shape, the courtyard, and the L-shape, each with a garden. Cerdá’s emphasis on green spaces predates today’s stress on LOHAS (lifestyle of health and sustainability) and sustainable living with ecological initiatives. While our goal is toward climate control, Cerdá’s was about common sense. And Cerda conceived it better: he had a height requirement to ensure adequate sunlight with each permutation. Commerce was to be on the ground floor, the bourgeoisie one floor above, and the workers in the upper floors.

Cerdá believed egalitarianism would be achievable with the classes learning and sharing from one another, exposed to the same hygiene conditions.

Ventilation and mobility were key points, and better yet, efficient sanitation systems were also achievable with the straight grid lines and chamfered corners of 45-degrees. The blocks were oriented northwest to southeast to maximize daily sun exposure. Cerdá not only reduced potential blindspots that would encourage criminality, he boosted a holistic liveliness for the barrio to support mental and physiological health. Each 20-square-block district was designed to be self-contained with shops and civic facilities such as hospitals, plazas, and gardens to accommodate interaction so people are not cut-off from one another. Hence, as goods flow, so would ideas. Multiple routes promote dispersion of foot traffic and street life. I find this a stark contrast to the engineering of Kuala Lumpur’s city irrigation systems, our morbid obsession with skyscrapers as well as total disregard for communal building. Our city is flood-prone with shambolic systems in place that mismatch the populace. And if it weren’t for the pandemic, ventilation and open spaces were often vetoed over covered and air-conditioned spaces. Rather than optimize the abundance of tropical weather, we blame it. Today, we are experts at building mental-health-traps as well as structures built at escalating costs for the vulgarities of tourism. In recent years, each time it rains incessantly, people experience post traumatic stress disorders fearing they could lose access to their vehicles, life, and livelihood.

Unfortunately, like many modern urbanization and gentrification stories, rivalry, politics, and greed eventually wrapped its insidious tentacles around Cerdá’s humanitarian endeavour. Oh, the royal government loved it, but in 1859, a plan by architect Antoni Rovira won over the city government. Aimed towards the mighty and the wealthy, Rovira’s plan returned to the traditional framework with the bourgeoisie in the center and the workers on the fringes of the city.

As the decades passed, Cerdá’s influences tried hard to pervade but throughout Barcelona they were abandoned with half-baked constructions and ill-advice. The Eixample got built nonetheless though many blocks became parking lots and shopping malls. They grew too loud and became overcrowded.

Still, Barcelona is Barcelona, a beast of resilience, artistic wonder and enduring beauty. According to Michael Neuman, Associate Professor of Urban Planning and founding chair of Sustainable Urbanism and a Cerdá expert, despite re-drawings, interventions, and political interference, the humanist engineer’s work has guided Barcelona’s growth for the last 150 years withstanding economic crises, change of regimes, and institutional neglect. That in itself speaks to contemporary architects, engineers, and designers.

I recall flying out of the city with a tinge of sadness not because my trip had come to an end. but as I looked down with a bird’s eye view from the airplane, I thought of the many wicked problems Cerdá could have solved: That cities could be built better with his templates, our quality of life increased, and support happier, healthier people. Unfortunately, it was us and our platitudes for hollowed veneers that chose to walk the other way.

Great article. The name is Eixample, not Ensanche. It symbolizes the vibrant Catalan heritage, while the imposed translation attempts to erase it. Celebrating linguistic authenticity and cultural identity!