You can read part one here, and part two here.

The batik is one of the oldest industries in Malaysia with records dating back to the early 1900s. The craft itself is over 2000 years old, and is the main contributor to the overall performance of craft sales in the country growing from RM143.5 million in 2010 to RM409 million in 2012 at its peak. Around 320 batik entrepreneurs are registered with the Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation (MHDC), a statutory corporation established in 1979 to promote the marketing and export of handicraft products with the highest concentrations of batik producers located in the states of Kelantan and Terengganu. Marketed as a tool for cultural tourism to boost coastal states such as Kelantan, Terengganu, Langkawi, Penang, and Malacca — the last two being heritage sites, batik may appear to be popular but there are severe gaps in its governance.

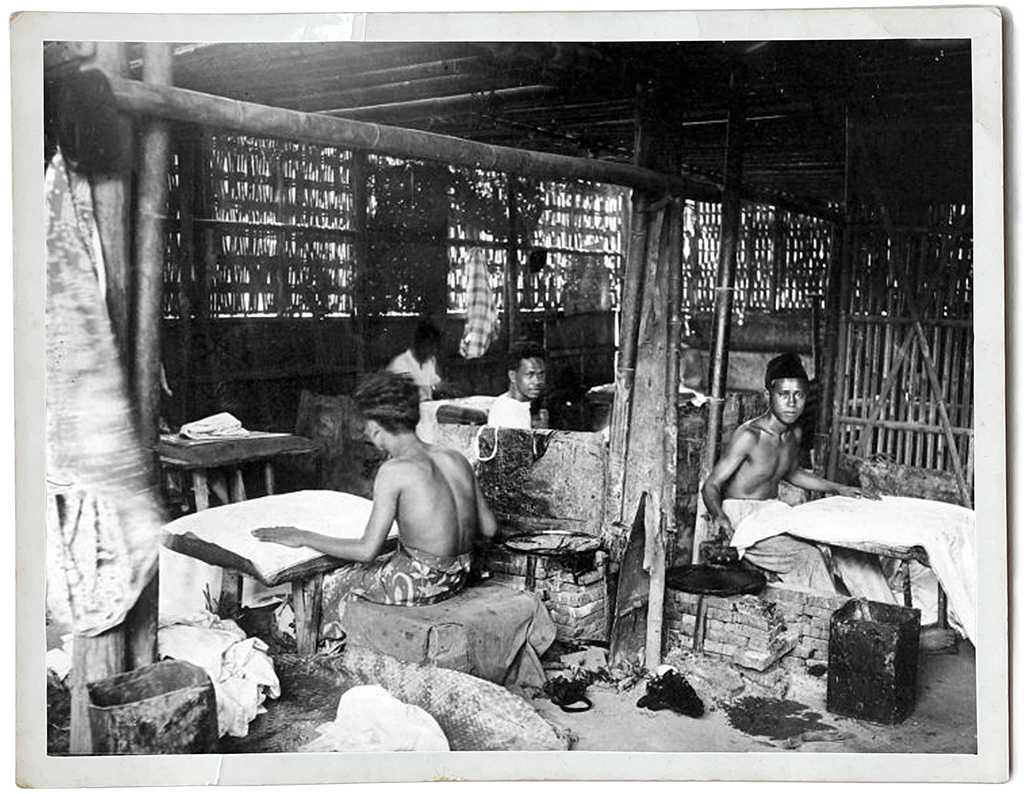

In recent years, both the craft and master craftsmen are inching toward extinction.

Historically, artisans were members of a guild that shaped the artistry of civilization. According to bonfire tales, they also had magical powers and thus, were highly revered. From pottery, carpentry, jewelry, leatherwork, metalwork, paintings, sculpting, and weaving, artisans created things that enriched the social fabric of a community. Artisans were said to possess supernatural abilities as artistry was deemed subjective and unpredictable. They worked in isolation only to reappear with something people could only imagine. For a society that was predominantly uneducated and pragmatic at the time, all things aesthetics were spell-binding. Artisans with very specialised skills were known as craftsmen. They were commissioned by the sultans and looked after by the royal courts. Sadly, as the industrial revolution evolved in the 1800s, machinery and mass production took over. Artisans slowly fell out of the ranks.

The batik industry is categorized in the manufacturing sector of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). If we look at the long term growth trend of SMEs in Malaysia since 2004, the SME Gross Domestic Product growth continuously outpaces the overall growth of the Malaysian economy with employment records showing more workers absorbed than in larger firms. With this classification, the batik industry is also expected to help the development of the Malaysian economy. But a trip to a batik site will tell you a different story.

As an entrepreneur dealing with the community, remove the veneer and you will realize that batik makers are more likely positioned in what is known as the informal economy. In layman’s terms, they’re sidelined, marginalised, with much of their life’s work undocumented.

According to the International Labor organization (ILO) the informal sector refers to “economic activities of workers and entities which are in law or practice not covered by formal arrangements.” In business terms, the informal economy can refer to “economic activities that occur outside the formal labour market that can include doing odd jobs or providing services for which the artisans are paid in cash.” Political factions have left Kelantan, thus leaving many of its artisans in the B40 community (the bottom 40% of the Malaysian household income). It is a hard fall from grace because these people are national treasures. They have skills we need to preserve and pass on to the next generation.

Too often ministries and stakeholders downplay the fact that the artisans are living hand to mouth with no safety nets to assure sustainability, safety, and long-term support. Most of what they do still depends on cash, word-of-mouth, or to serve as tokens for government-linked projects. Luckily, foreign tourists are drawn to the rustic, provincial, and traditional narrative which have been a form of life support. Unfortunately, these protections were gone when Covid-19 happened and the tourists disappeared.

Here, we speak highly of artisans but we offer them little safeguarding.

But the pandemic showed gaps that we can no longer ignore. During the first lockdown itself we witnessed a catastrophic flaw in the systemic structure compared to how artists are treated overseas as in Germany and Canada. Here, we speak highly of artisans but we offer them little safeguarding. They are not taught how to weather their businesses, protect their intellectual property against the forces of digital printing, or offer information on ways to scale without being cheated by the middle men. Next, many artisans are off the grid. Not being registered in the government system means they are without any kind of retirement, medical, or social security provisional funds (SOCSO and EPF). Many still keep their money at home under their mattresses instead of in a bank. Indisputable efforts have been arranged by organisations and generous foundations such as Yayasan Hasanah and MyCreative, but missing are enforcement, connectivity, and a blueprint. Despite many financial aids circulating online, many hard pressed artisans are cut-off from the communication because they are out of the digital infrastructure.

Talks of a new normal will be the greatest challenge for the local cottage industry as purpose-driven innovation, digital literacy, and a systems change that are needed for artisans to remain relevant. To do this, we need collective intelligence. However, the Movement Control Order raised pain points to a scale that they can work to an advantage. For instance, the state of poverty in Kelantan is not new and we now see the depth of the problems. Agencies and governments have been coerced to see the need for speedier remedial efforts. Previously, it would have been reduced to an administrative stockpile.

Whether or not arts and crafts are deemed “essentials” depends on who is asking. As borders reopen, the tourism industry, present employment, and batik entrepreneurs can be the third party to help ameliorate this situation.

The entrepreneur’s role should be to seek projects that can be broken down into as many different job opportunities as possible. For example, aside from hiring people for batik making and as batik workshop trainers, artisans can do homestays, be placed under Airbnb Adventure in order to attract more visitors. The adventure programme can enlist the help of a local guide/host and include many avenues to expose local businesses like the pakcik selling barbequed beef by the roadside, the makcik selling nasi air, and the local masseuse offering traditional healing.

Another impediment to the deep-dive is the environment that lacks entrepreneurs to look into wastewater management together with learning institutes, non-government organizations (NGOs), and researchers. Material, processes, procedures, dyes and disposals in the batik industry can lead to controversial discussions. Synthetic dyes used in batik are loaded with heavy metals necessary to increase the bonding strength between dyes and fabrics. Unfortunately, they cannot be decomposed by microorganisms. Although not everyone in the informal economy is poor, a significant proportion are, and the occupational risks are compounded by factors such as a lack of sanitary facilities, and a lack of basic health services. For many artisans their home and workplace are one and the same place, therefore resulting in a combination of undesirable living and working conditions.

Exposure to toxins range from melted wax fumes, the handling of sodium alginate, soda ash, calsolene oil and synthrapol, to dug well water contamination due to infiltration of batik wastewater and poor construction. Vulnerability to diseases and poor health impinge on production leading to disruption of income.

In the future, many say we should prioritize going digital and redesigning customer touch points to promote batik. I recommend emphasis on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Batik production is part of the textile industry deemed one of the biggest polluters in the world. Its annual carbon footprint of the fashion industry’s product life cycle is 3.3 billion tons of CO2 emissions. In terms of consuming huge amounts of resources, the textile industry is responsible for 5% of the global volume waste. The proportion of textile waste that goes to recycling today is greatly insufficient for the system to be called circulatory. A pivot for batik makers and entrepreneurs is no different to textile manufacturers to pursue sustainable development strategies, and to transition to the circular economy (CE). Goal 12 (responsible consumption and production) tasks in particular are believed to ultimately reduce the volumes of waste through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse. Batik producers will need to establish this in their business’ value propositions.

Many ask, “Why isn’t Malaysian batik reaching into the European market with the promotional efforts of MHDC? To answer that, we need to answer these questions as well:

- Do batik producers conduct good practices?

- Does local batik production comply with the standards of international occupational safety and health (OSH)?

- Do batik entrepreneurs have mission statements or mottos containing references to sustainable development?

The latter is one of the strategic criteria for being a circular organization. Europe, more than the rest of the West, has high levels of quality control. Environmental awareness as well as understanding the transition to a sustainable business model are critical for a competitive edge and necessary for approval by the European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (a joint initiative by the European Commission and the European Economic and Social Committee).

In short, what happens to leftover batik is just as significant as how we produce batik. This brings us to upcycling and recycling. Moving forward, used textiles should be seen as a valuable resource to create new business opportunities and must be designed in a way that fosters repair, re-use, and recycling which have a low impact on the environment.

Closing the chapter to the series I would like to say that the reverence for batik has never waned. Perhaps best seen as modern alchemists rather than magicians — watching them work remains spellbinding. You can still feel the aura, the presence of ancestry, and the good old magic wafting in the coastal breeze. And just as the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach placed the Templars at the heart of his King Arthur story, Parzival, as the defenders of the Holy Grail, there will always be protectors of batik and other traditional textiles. You can be one of them.

A damning indictment of lost opportunity and of living heritage. Fantastic article Natasha.